Cine-zoonosis: screening human/animal pollinations and contaminations

Call for papers

During the COVID-19 pandemic, epidemiologists and ecologists have repeatedly warned that, as climate change continues to decimate wildlife and their habitats, global pandemics resulting from animal-spread disease will inevitably become more common.[1] A “zoonotic disease” is one that has the capacity to “jump” back and forth between human and animal populations. As is now abundantly clear, such diseases have the potential to dramatically disrupt society, kill hundreds of thousands of people, exacerbate existing social conflicts, and set the political agenda for years to come. Consequently, zoonosis is a pivotal site in the ecopolitics of our current moment—a space where the pressing issues of rapid species extinction, national borders and migration, land management and conservation all intersect.

In this anthology, we conjoin zoonosis and cinema, asking how they mutually define and illuminate each other—historically, theoretically, aesthetically, and politically. On the one hand, public health institutions like the Center for Disease Control have long used film as a tool for studying and combating zoonotic disease. In this sense, the history of cine-zoonosis is deeply wrapped up in the history of medicine onscreen, analyzed by scholars such as Kirsten Ostherr and Lisa Cartwright.[2] In these settings, film has been used to study infected humans and animals, as well as to inform the public about the threat of zoonotic diseases (such as rabies) and about preventative measures people should take to deter their spread. In such films, animal images become tangible avatars for diseases which are otherwise invisible – or only visible within the abstract world of micro-cinematography. The animal becomes a stand-in for the disease which can be observed and interacted with at a human scale. As a result, the techniques used to frame the animal as a disease vector are crucial for the interspecies implications of each film. Cine-zoonotic representations of this sort intersect with and often draw from other histories of animal representation through film, such as those of the wildlife documentary. Public health organizations such as the CDC frequently adapted strategies for visualizing animals from popular documentaries of the time, a phenomenon explored by scholars such as Derek Bousé, Cynthia Chris, and Gregg Mitman;[3] as well as the strategies for representing animals deployed by laboratory scientists and educational filmmakers, like those analyzed by James Leo Cahill, Jennifer Peterson, and Oliver Gaycken.[4] On one hand, then, our collection poses the question: what can these visualizations of zoonosis tell us about the line we continually seek to draw (and efface) between human and non-human animals, about the difference between “us” and “them,” and about how we value different forms of life and consciousness when our own health and/or survival may be at stake?

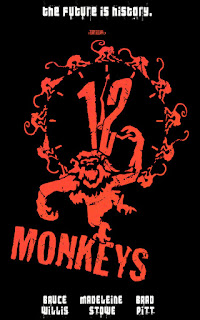

The concept of cine-zoonosis, on the other hand, can also be understood in terms of a more metaphorical imbrication of humans with other animals as it has been explored through cinema. Critical animal studies scholars have long discussed and debated the ideas of cross-species infection, penetration, and mutual transformation. From Donna Haraway—who begins When Species Meets with the recognition that her dog “continues to colonize all my cells”[5]—to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari—who describe “becoming animal” as entering into a “particular zone of proximity” in which individuals are clearly made inseparable from “the fog and mist that depend on a molecular zone, a corpuscular space”[6]—the topic of the interpenetration of human and nonhuman animals has been of central concern. Theorists working to bridge the gap between critical animal studies and film studies have sought to apply such ideas to the relationship between onscreen animals and human spectators. Akira Lippit writes of onscreen animals as “animetaphors,” which spark an unruly process of identification and alienation between viewers and cinematic images of animals. Meanwhile, Anat Pick describes what she calls the “creaturely poetics” of onscreen animals, which can force a sense of shared mortality and finitude between human audiences and the animals they watch.[7] Thus we also wish to ask: what happens to such moments of contact when placed within the context of “cine-zoonosis,” particularly as these encounters are explored in science fiction and experimental films?

The concept of “cine-zoonosis” takes on a particular set of urgent political stakes within our contemporary moment of ecological collapse. As a major effect of changes in the Earth’s biome, zoonosis becomes a central site for contemporary global biopolitics—part of what Neel Ahuja calls “the government of species.”[8] The answers to questions of who will or will not be exposed to zoonotic diseases, who will or will not be given vaccines for these diseases, as well as who will be the test subjects when developing them, will have major impacts on lives in the near future. As a phenomenon, zoonosis has the potential to upend and rearrange the exploitation of humans and animals, but it also can clearly intensify such forms of oppression. As a historical development closely tied to climate change, the rise in zoonotic diseases asks for a critical approach to the ways in which our media ecosystems produce knowledge and understanding of this perceptually inaccessible threat in a range of settings. At the same time, knowledge of human vulnerabilities and culpabilities have long been a lived reality for people and communities who suffered the first consequences of resource and labor extraction along with the planet: the indigenous, the enslaved, the colonized, the bonded and migrant laborers, the Global South. Ways of knowing and living with the animal and the more-than-human that precede, interrupt, reinforce, or supercede contemporary institutional, rationalist, and scientific models become important in this context. The contemporary disease vector that draws our attention to “cine-zoonosis” emerges as a product of environmental abuse that was never, by any means, the only way to coexist with the environment.

We therefore also invite submissions that consider how zoonosis as a phenomenon impacts the production of images of humans and nonhuman animals in our current media milieu; how this shifting relationship is represented onscreen in different settings across the globe; and how this present visual context makes us reimagine our collective human as well as more-than-human past or future.

Possible topics include, but are not limited to:

- Cinema as a tool for visualizing zoonotic disease

- Case studies of public health films made about zoonotic diseases

- How images of infected animals are created and circulated

- Cross-species relationships theorized as infections or contaminations in cinema

- Global and local disparaties in visualizing human-animal pollinations

- Institutional and infrastructural histories of contemporary zoonotic representations

- Indigenous and intersectional critiques of zoonotic public health films and programs

We invite interested parties to submit chapter proposals for essays of approxamitly 5,000 words in length. Proposals should be 250-300 words and are due on September 30th, 2022. Please email your submissions to the book’s editors: Benjamín Schultz-Figueroa (schultzfigub@seattleu.edu), Jaimie Baron (jaimie1@ualberta.ca), and Priya Jaikumar (pjaikumar@cinema.usc.edu). Decisions will be announced in December, 2022 with the goal of receiving completed chapters by the end of Spring, 2023.

[1]. Inger Andersen and Johan Rochstrom, “COVID-19 Is a Symptom of a Bigger Problem: Our Planet’s Ailing Health,” Time, June 5, 2020, https://time.com/5848681/covid-19-world-environment-day/; John Vidal, “‘Tip of the Iceberg’: Is Our Destruction of Nature Responsible for Covid-19?,” The Guardian, March 18, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/mar/18/tip-of-the-iceberg-i....

[2]. Kirsten Ostherr author, Cinematic Prophylaxis: Globalization and Contagion in the Discourse of World Health, E-Duke Books Scholarly Collection (Durham, Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2005); Kirsten Ostherr, Medical Visions Producing the Patient through Film, Television, and Imaging Technologies (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2013); Lisa Cartwright, Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995).

[3]. Derek Bousé, Wildlife Films (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000); Cynthia Chris, Watching Wildlife(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006); Gregg Mitman, Reel Nature: America’s Romance with Wildlife on Film (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1999).

[4]. James Leo Cahill, Zoological Surrealism: The Nonhuman Cinema of Jean Painlevé (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019); Jennifer Lynn Peterson, “Glimpses of Animal Life: Nature Films and the Emergence of Classroom Cinema,” in Learning with the Lights off: Educational Film in the United States, ed. Devin Orgeron, Marsha Orgeron, and Dan Streible (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 145–67; Oliver Gaycken, Devices of Curiosity: Early Cinema and Popular Science, 1 edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[5]. Donna Jeanne Haraway, When Species Meet, Posthumanities 3 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 15.

[6]. Gilles Deleuze, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 273.

[7]. Akira Mizuta Lippit, Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000); Anat Pick, Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011).

[8]. Neel Ahuja, Bioinsecurities: Disease Interventions, Empire, and the Government of Species (Duke University Press, 2016), 10.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire